Our Bagri Hub

By the banks of the Black Volta River, the women of Bagri Junction wash their clothes while men fish in wooden canoes downstream. The river’s highest verges are lined by dry season farms, where labourers tend to crops and assess the damage caused by hungry hippos visiting the previous night. When the afternoon sun starts its retreat, a stream of fishermen, farmers and housewives make their way back home heavy with the day’s labour. The river, which bends around the three villages of Bagri Junction, shapes the community’s way of life; their daily ritual undisturbed by a world racing ahead without it.

Some residents are more stubborn than others to defend their traditions. Despite a number of recent borehole projects supplying the community with water, some insist on drinking from the river: they say it “tastes sweeter!” Others warn against it, reporting concerns about mercury pollution carried from careless mining operations upstream. Either way, there are greater environmental challenges to worry about. Climate change is interrupting the seasons and impacting farming in turn. Crops are devastated as the monsoon months are cut short by extended periods of punishing heat. The challenge is growing every year for the large population of subsistence farmers at Bagri Junction; whether you sow your seeds at the right time is increasingly down to sheer luck, rather than skill.

But for those farming by the riverside, it’s a different story. If you’re able to pump water from the river, you’re given more cycles of production before the rains flood the farms. ATE supports two dry season farmers in Bagri Junction and both are growing more than ever before. Sebastian, an ATE supported farmer since 2019, is now turning enough profit to feed his family all year round and is able to put money aside for equipment too. He harvests pepper, watermelon, pumpkin, cassava and even sweet potato, which are taken for sale at the market in nearby Lawra. The mentorship and water-pump delivered by our programme is empowering him to take his future into his own hands.

But to keep growing and ultimately hire labourers, Sebastian needs more tools. This isn’t easy when the nationwide escalation in illegal gold mining (known locally as galamsey and what Sebastian describes as a “menace”) is inflating the price of agricultural equipment. He tells us that, “the demand for irrigation pumps, which they [the mine owners] use for drawing water out of the pits, has increased prices by 25% this year alone”. It’s no wonder that Sebastian, who is also chief of his village, Tabier, feels the way he does; especially as Bagri Junction’s teenagers are putting their lives at risk working on galamsey during the pandemic. This said, the growth of dry season farming in the area does mean that a handful of young labourers are avoiding dangerous work in the south and can even earn more in doing so. This is hopeful, but it’s far from a solution: there simply isn’t enough work to meet the scale of school dropouts at Bagri Junior High School.

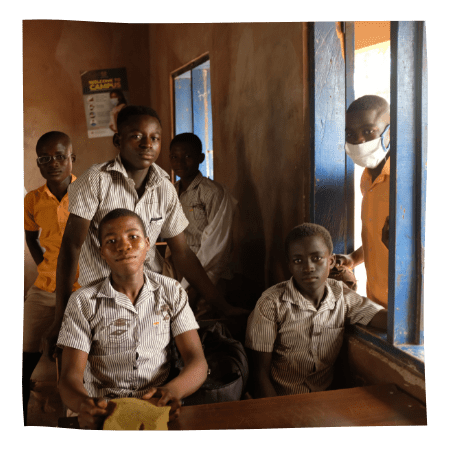

We’ve supported Bagri JHS with our school feeding programme since 2019. Early signs were promising and attendance started to climb, but the pandemic knocked progress. School turnout dropped from a high of 90% in February 2020 to just 50% a year later. The figures are even more troubling in older years: Form Three (aged 14 to 15), for instance, went from 20 to only five students. These are some of the worst numbers reported in the region. So, why is attendance so low in Bagri?

There is a myth among locals that their community is cursed. As undisputed as the yams in the soil, this conviction has been cultivated by years of perceived misfortune. At our Hub community meetings, residents lament the fact that while the area has produced successful people, they never return; the wealth never shared in the place they once called home. This is not unusual and we often hear similar grievances from our other rural Hubs. Yet in Bagri, people’s resignation to their curse is strongest. Does this influence school attendance? We think so. First and foremost because it’s affecting the parents’ attitude towards education. The common feeling is: what’s the point in education, if we, as a community, don’t see the benefits? This became clear in a meeting with parents on school dropouts. What started as a blame game (“the main problem is the existence of mobile phones”, said one parent) turned to an admission from the PTA Chairman: “the problem is from we the parents. We fail to control our children.” Without faith in the fundamental reasons why their children attend school, parents are struggling to encourage them to go.

Poverty is at the root of why Bagri Junction feels its misfortunes so profoundly. Yet the short 10 minute ride from Lawra is enough to sense that its fortunes may be changing. Fresh tarmac covers roads running parallel to newly strung electricity pylons; a national solar panel project (commissioned in 2020) on the outskirts reclines in the sun, while shiny tin roofs atop mud houses reflect it back. Although such investment is unlikely to change the local people’s traditional way of life, it’s nonetheless a welcome sign of development. ATE’s Hub approach in Bagri Junction empowers people to recognise their potential as individuals and as a collective. With a familiar, knowledgeable and reliable presence in the community, we hope to help the villagers of Tabier, Konwob and Orbile, believe in the future of the place they call home; to see life in Bagri as a blessing, rather than a curse.