Our Dowine Hub

The centre of Dowine (pronounced “Dom-win-ee”) has the buzz of two worlds colliding. The weekly market which hums with the time-old sounds of sensen sizzling in a pan, of impatient livestock demanding to be untied, and of market hawkers touting their goods, now competes with the noise of modernity. A sound system, run by young electronics traders, plays Ghana’s top of the pops beside a junction where HGVs roar by on their way to the Sahel. Drowning out tunes with their industrial boom, this daily stream of lorries is leaving a permanent mark on the dirt road they pass over. The rugged highway is becoming desperately impractical, damaged and dangerous for those who live there.

Kwame Imabong, a severely disabled SNAP member in his early 30s, sits everyday under a mango tree by the road to beg. His mother, Kaale, who sells rice at the market, remarks, “there have been many times where Kwame has almost been hit. But there’s nothing he can do because he cannot move out of the way. The road has to be fixed.” A makeshift speed bump, made by concerned villagers has succeeded only in sending motorbikes and minibuses (known as trotros) skywards as they fly past. Kwame’s wheelchair is unmotorised which means getting into town is another uphill struggle. He has to find someone to take him on a trip that can take hours, which then comes at a price to him and his mother. While we’re taking steps to secure Kwame a wheelchair that will afford him greater independence, there’s little we can do about the road he travels on. Over the years, the crossroads at Dowine has come to reflect its difficult position as a community; itself at an intersection between the old world and the new, it needs support to pave a steady way forward and realise its potential.

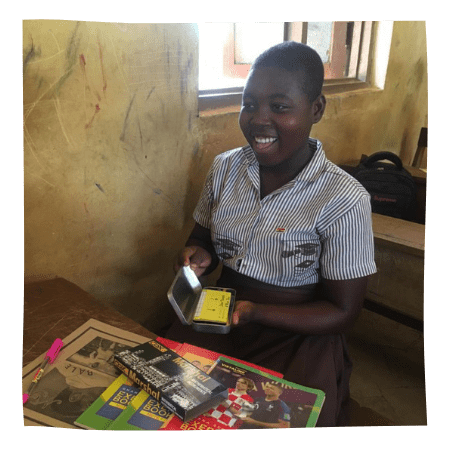

This is most clear in the successes and challenges faced at Dowine Junior High School. An ATE supported school from 2016, we’ve been able to truly embed our EducATE programme there ever since. Our school feeding facility and the provision of learning materials and uniforms have been instrumental to its high attendance and we’re proud that the majority of students now have the means to go to senior high school. But like every school in Lawra, the pandemic knocked progress. With one less meal a day and little to do, students worked in dangerous jobs in southern cities or on illegal gold mines (known locally as galamsey); some stayed at home but took up a trade instead. As of May 2021, 28 students were yet to return. The grind of poverty and the lure of quick money has led young people to fall out of love with education over the nine month closure, and choose to work, often at risk.

Dowine JHS is doing everything to turn this around and headteacher, John Bosco, is creating a learning environment that is inclusive and engaging. But nothing is ever easy. He built a computer room to prepare for the delivery of laptops, only for the dimensions of the room to be rejected by the authorities and the availability of PCs dry up. Then, he secured textbooks for the new curriculum, only to receive no training or explanation on its content. Laughing, Bosco says, “some of the students know more about the topics than the teachers! The opposite happened at the primary school; teachers received the training, but not the textbooks!”

Where it can be, however, the school leadership is proactive and driving change. Students recently produced their own-brand ‘Dowine JHS Liquid Soap’, tying together chemistry and hygiene-awareness. They can take up an instrument thanks to a music room equipped with a traditional xylophone and trumpets. The teachers are holding an end-of-year awards ceremony for pupils’ achievements and the leadership is even applying for funding for an on-site clinic to fill a former school building next door. Headteacher, local assemblyman, and most importantly, a role model in the community, John Bosco lives up to his saintly namesake as a patron for local schoolchildren. Yet by his own admission, there’s only so much one individual can do: “at the end of the day”, he says, “it’s the parents who sleep in a house with the students, not the teachers.”

This is why our community-first Hub model is key to putting Dowine back on track. As our longest-supported community outside of Lawra, we’ve turned quiet aspirations into visible success stories. Since 2016, thriving small businesses have popped up around the village and are employing apprentices as they grow; Mercy, for instance, is an ATE supported seamstress who now trains a team of 14 at her workshop, as well as leading the union of seamstresses in Jirapa (read her story here). We’re mentoring and funding projects for dry season farmers on the rural outskirts, and we hold our largest SNAP meeting and playgroup at the school every month; the importance of which was highlighted in 2020, when our team took a SNAP mother, a victim of a domestic abuse, to a hospital in the nearby city of Wa for an emergency operation. Our work in Dowine shows that community development is best when we work closely together. With or with-out major challenges like the pandemic, there’s always work to be done.

Dowine, like Lawra, is a community built on a crossroads. The sun-scorched track that leads from the municipal capital, beelines under towering Rosewood trees and ascends through the large, rival communities of Zambo and Eremon. A shortcut between two parallel north-south highways, Dowine has an advantage no other rural Hub has: people pass through it. Lifting the village out of poverty and building the foundations of a strong road into the future, rests partly on harnessing this advantage so that people don’t just pass by, but stop, engage and maybe even stay.